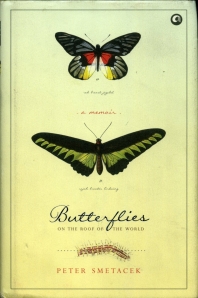

Hiren Kumar Bose quizzes author Peter Smetacek of Butterflies on the roof of the World (Aleph), on chasing butterflies and how change in their population affects biodiversity

Having spent a lifetime collecting/studying butterflies (and moths) what do you think is their role in the country’s biodiversity?

Having spent a lifetime collecting/studying butterflies (and moths) what do you think is their role in the country’s biodiversity?

Insects form the largest group of life forms on earth, outnumbering all other life forms put together. Butterflies and moths are the second largest group of insects, after beetles. Naturally, no biodiversity count can ignore them. The services they give to the ecosystem are pollination, but perhaps the larger role is the fact that caterpillars, pupae and even eggs are the prey base for a large number of birds, spiders, wasps and other insectivores. A change in the population of butterflies and moths will naturally be reflected in a corresponding change in the population of the creatures that prey on them.

We all are aware about the Tiger’s role in biodiversity but ignorant on the importance of the insect world. Why it so?

The reason for this discrepancy is of course that the tiger is much larger and has been historically feared by our species. The reason that the insect world has been largely ignored is that it is not glamorous or adventurous nor does it generate empathy in humans. In the popular imagination, chasing a butterfly is not as exciting as being chased by a tiger. Students that join an entomology course in our country are often diverted into specializing in insects of economic importance, such as agricultural pests. Insects that inhabit our forests and other natural habitats are thus largely ignored. Given the lack of basic information on them, it is no wonder that the Indian public is ignorant of the insect world.

Their short life spans, their size and being lower in the food chain have gone against them. Comment

Their short life spans, their size and being lower in the food chain have gone against them. Comment

All these three factors might have variously impacted the lack of interest in insects, but perhaps the most important was the need to collect specimens to study them, which is abhorrent to the average Indian. Since the development of digital photography, there has been a major spurt in interest in the smaller creatures, including butterflies. In fact, it may safely be stated that never before have there been so many people out in the field observing butterflies and moths as there are now. This welcome news is the direct outcome of the spread of digital photography.

Being owner of the largest individual collection of butterflies of the Indian sub-continent, do tell us about those whom you consider as your prized catch?

The prized specimens of any collection are type specimens, that is, the specimens on the basis of which new species or subspecies have been described. I am lucky to have a large number of these so undoubtedly, these are the centerpiece of the collection!

The beautiful looking butterflies you have come across.

India has a vast number of beautiful species. This is what attracted my grandfather and father to the field to start with. However, since beauty is largely in the eye of the beholder, you will excuse me if I do not press my point in this matter. The Common Peacock (Papilio bianor) received the most points during an election conducted by the late M.A. Wynter-Blyth, one of the doyens of the science in India. Therefore, I gave it the title of being the most beautiful Indian butterfly when I was consultant for the Limca Book of Records.

A pioneer in the use of Lepidoptera as indicators of climate change, do tell us how they are faring and what we need to save them?

There are several interesting changes going on, such as the colonization of the Himalaya during the last decade by the Red Pierrot butterfly (Talicada nyseus) and the eastwards spread along the Himalaya of the Bath White butterfly (Pontia daplidice). On the whole, India is believed to be getting warmer and wetter, which is good news all around, for butterflies and moths as much as for our agriculture. The only danger here is the probable increase of floods and subsequent droughts, since our forest cover (as opposed to ‘green cover’) is pitiable and healthy forests which can support perennial water sources and consequently, healthy butterfly communities, are few and far between. Our government does not seem to have any effective idea or plan to remedy the situation.

You’ve discovered and describe three new butterflies, namely Neptis miah varshneyi, Neptis clinia praedicta and Mycalesis suaveolens ranotei. Do tell us the story behind it?

All three are long stories which might find a place in future books, but briefly, the first was discovered when it became apparent that the butterfly identified as Lasippa viraja was actually Neptis miah. Since the known forms of Neptis miah differed considerably from L. viraja, it became clear that this near perfect look-alike of L. viraja needed a name to distinguish it from other populations of N. miah.

In the case of the second, the late Lt. Col. J.N. Eliot had obtained a specimen of N. clinia from Dehradun, which he suggested was a new subspecies. When I obtained further specimens, it became clear that it was different from Eastern Himalayan populations of the butterfly, so I called it N. clinia praedicta, to commemorate Col. Eliot’s prediction.

In the case of M. suaveolens ranotei, I obtained a male butterfly during a survey and when looking to see whether there were any other records of this butterfly from Uttarakhand, came across the female of the species collected by Dr. Arun Pratap Singh Ranote. Therefore, I named the subspecies Mycalesis suaveolens ranotei. So far it is known only from the original pair.

Do enlighten us on the activities of Butterfly Research Centre?

The Butterfly Research Centre has a reference collection of Asian butterflies and moths. We get specimens from research institutions and individuals all over the country for identification. It is open to public viewing and we usually give an introductory talk about the butterflies, their habits, mimicry, variation, survival strategies, etc. Besides, we run beginner and advanced level courses, which are customized to suit the needs of the students (who range in age from teenagers to professionals wishing to expand their repertoire). Generally, the courses cover curation, identification, zoo geography, taxonomy, habitat identification, etc. In addition, we undertake surveys of Lepidoptera.

Chasing butterfly is not a lucrative or a paying career but you have kept at it for over four decades now, thanks to your consuming passion. Your message to young lepidopterists.

As I have mentioned in my book, I began to spend more time with Lepidoptera when there was a need to re-build the family collection after it had been destroyed in 1980. During the 1990s, I might have examined other career options, but my wife and I were targets of a criminal gang who were not only very well-connected at all levels of society, but were involved in the gamut of crime, from drug dealing to terrorism. Their interest was to make our home into a Maoist training centre, after disposing of us. By God’s grace, we survived and their plans came to naught. During that time, there was little to do except study moths and butterflies, while I was teaching at a school run by Vidya Bharati, near Nainital. When the danger had passed, I stopped teaching and have devoted myself full-time to this pursuit since then. Even today, being a lepidopterist is not a well-paying or glamorous career. I would not recommend it as a career option to any except those ‘touched’, but would definitely recommend it as a very engrossing hobby and passion!

An edited and shortened version was published in btw (www.btw.co.in) February 2013 issue